This report from Windward, the leading Maritime AI™ company, offers proprietary insights from our artificial intelligence platform illuminating how Russia’s year-long war with Ukraine has impacted deceptive shipping practices (DSPs), trade routes, and more.

Executive Summary

This report from Windward, the leading Maritime AI™ company, offers proprietary insights from our artificial intelligence platform illuminating how Russia’s year-long war with Ukraine has impacted deceptive shipping practices (DSPs), trade routes, and more.

The West has remained relatively unified and measures such as the oil price cap are working: the average monthly number of tankers that had a port call in Russia and subsequently called port in the U.S./EU/UK decreased by 34% post-invasion. But countries such as India, China, and South Korea have obviously not agreed to comply with sanctions and the data shows a significant increase in their engagement with ships that had recently called port in Russia.

Additionally, while we did see a significant decrease in direct port calls in the U.S., EU, and UK from vessels that had called port in Russia, there is a bit of a loophole. Since the war began, the number of shipments arriving through ship-to-ship (STS) engagements has remained steady, despite the oil ban and price cap regulations. This is likely related to the “dark fleet,” a group of vessels operating in the shadows by using DSPs, such as GNSS manipulation, to move sanctioned commodities.

The report’s deep dive into DSPs looks at dark activities, GNSS location manipulation, and more, and is divided into regions: the South Atlantic, the Black Sea, and a new hub for smuggling Russian oil, the Alboran Sea. The Alboran Sea has seen a significant increase in the number of STS operations by crude oil tankers since the war commenced.

A real-life case study of a Cameroon-flagged vessel demonstrates a combination of DSPs that many vessels are now adopting: loitering in areas advantageous for eventual oil smuggling; significant draft changes without registered port calls, indicating semi-dark STS engagements; and GNSS manipulation to obscure actual voyages and locations. The report highlights a key factor for uncovering grain smuggling from Ukraine and details an alleged grain smuggling operation. Lastly, Windward looks at the increasing maritime cooperation between Iran and Russia, analyzing an instructive case study.

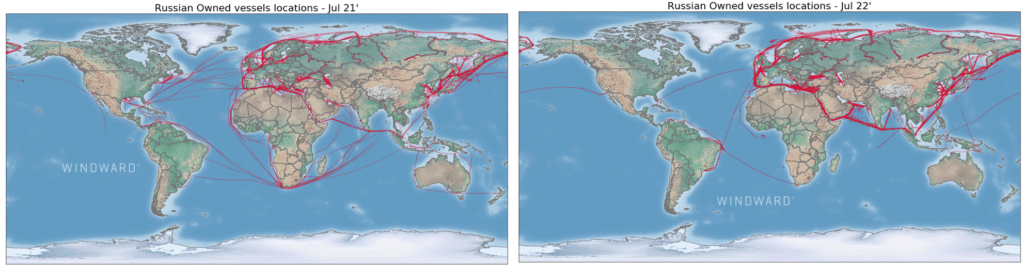

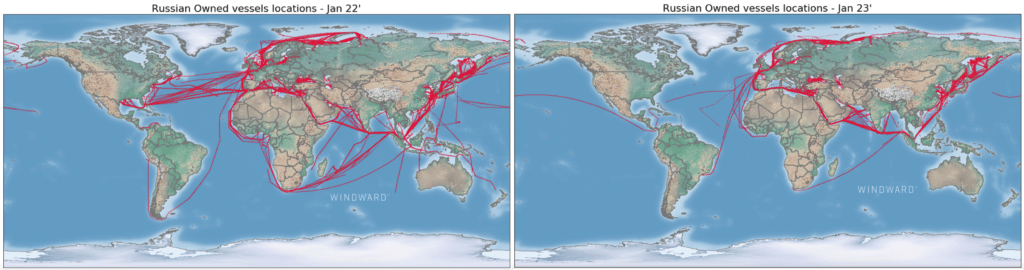

A deeper look into Europe shows some interesting trade flow shifts:

- The Scandinavian and Volga-Don straits have remained unaffected by the war and oil restrictions

- Trade moved to the Mediterranean sea

- The northern side of Europe seems more active in 2022 – an interesting hub to keep an eye on

Port calls are another indicator of the effectiveness of the West’s attempts to limit Russia’s profits. For instance, by looking at vessels that called port in Russia and then called port in the U.S., UK, or EU, we learn that:

- Before the war, 496 cargo vessels (monthly average) called ports in the U.S./EU/UK after a port call in Russia. This number dropped to 241 post-invasion, a decrease of 51%

- The average monthly number of tankers decreased by 34% when comparing pre- to post-invasion. The greatest decrease was among crude oil tankers

Unlike the West, India, China, and other countries in Asia have maintained more supportive, or at least more ambiguous, policies toward trade with Russia. As a result, a zoom-in on India, China, and South Korea shows a significant increase in engagement with ships that recently called port in Russia.

- 182 cargo vessels (monthly average) called port in Russia pre-war and then continued on to India, China, and South Korea. This number rose to 270 post-invasion, an increase of 49%

- The average monthly number of tankers along these same routes increased by 48% when comparing pre- to post-invasion

Ports in North Africa also illuminate this trend. Since the beginning of the war, there was a 147% increase in port calls of tankers from Russia – most of which are crude oil tankers.

The trade flow and port call findings show that while the West has been diligent and unified about maintaining sanctions, the East is keeping business moving. How do deceptive shipping practices (DSPs) fit into the picture?

When we frame the numbers in the context of sanctions evasions, it’s clear the increase is related to Russia. In December 2021, there was one STS operation between tankers that both called ports in Russia prior to the meeting, compared to eight such meetings in December 2022.

The top four flags of tankers engaged in STS operations in the Alboran Sea are quite similar to those that operate in the Black Sea: Malta, Liberia, Panama, and the Marshall Islands.

When we compare this newly identified area to the South Atlantic (the previous popular hub of STS operations for smuggling Russian oil), we clearly see the similarities. Alboran has become a main hub for Russia-related illicit activity.

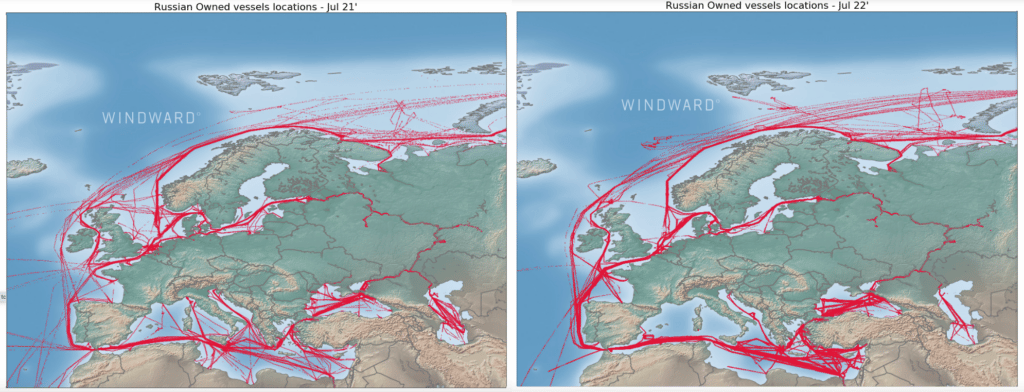

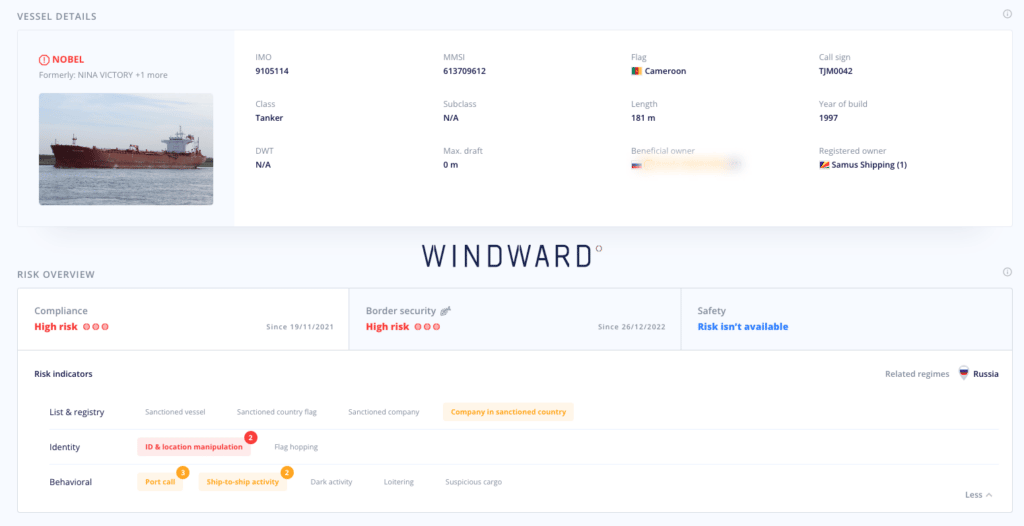

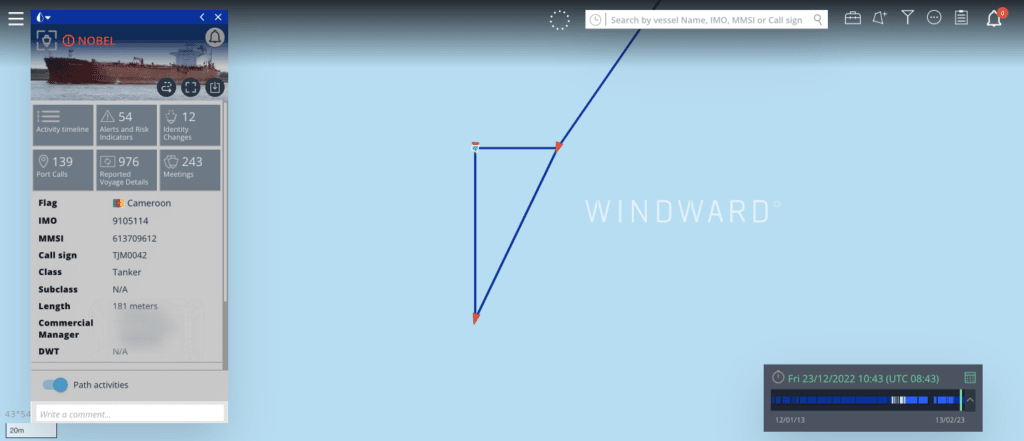

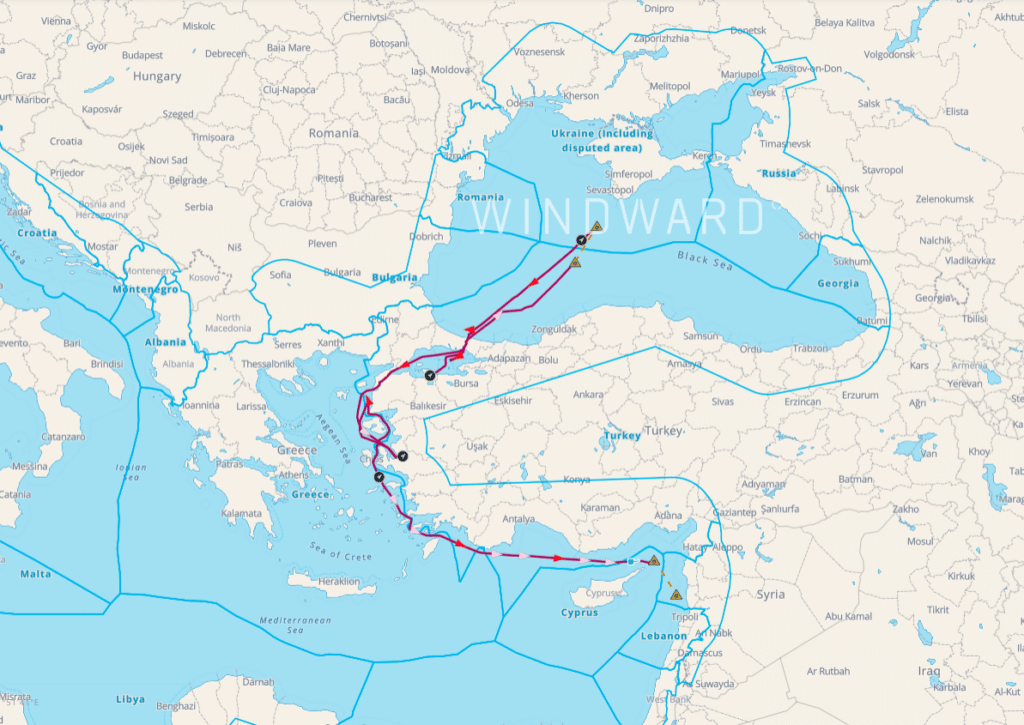

The Nobel was identified as loitering for three days in the Mid-Atlantic polygon in October 2022, without any economic or commercial reason for being there. It then did a course deviation and loitered for a few more days off the shore of Malta. Following these two loitering periods, it updated its draft from 7.5 to 12.0.

There were no reported port calls or STS engagement, indicating it received oil from a semi-dark activity (the other party/parties likely had its/their AIS disabled) either in the Mid-Atlantic, or Malta.

Following its suspicious draft change and after a few course deviations and meetings with cargo vessels, the Nobel called port in Turkey for five days in November 2022. It updated its reported draft to 7.4, indicating it discharged oil in Turkey.

On November 25, the vessel entered the Black Sea and then anchored in Russia for 13 days. A day after its departure, it updated its draft to 0, and a day later again to 7.4 – without any reported STS engagements or port calls. What was it carrying?

On December 11, the Nobel began manipulating its location, until December 29, when it reported another increase in draft, to 8.7.

Following the GNSS manipulation, it met with a few tankers, until it left the area on January 25, 2023.

The Nobel entered the new hub we identified, offshore Ceuta, on February 5, and as was also published in The Maritime Executive article, had an STS meeting on that day with the Elephant, a Vietnamese-flagged vessel. The Elephant has been flagged in our system as a moderate risk due to its meeting with the Nobel, and a few port calls it previously made in Russia.

Following the meeting with the Nobel, the Elephant updated its draft from 10.7 to 15, and immediately continued to a second meeting with another vessel. Following this meeting, the Elephant updated its draft again to 13.8.

Following these two meetings, the Nobel remained in Ceuta and was currently drifting there as of February 15.

It’s interesting to note that while the third-party vessel was detained for being involved with the Nobel secondhand, the Elephant, which had a direct interaction with the sanctioned vessel, called port in another Spanish port, Ferrol, on February 11. Indicating the smuggled Russian oil made its way to Spain after all.

Maritime risk is dynamic and it is of course influenced and impacted by huge world events, such as a world power invading a sovereign country and the resulting sanctions. It changes quickly and it is nearly impossible to keep pace without predictive analytics and artificial intelligence (AI).

This singular case study is indicative of the trends and combinations of DSPs Windward is seeing from vessels attempting to evade sanctions and capitalize on Russian oil and oil products trading.

Loitering in areas that would be advantageous for oil smuggling; significant draft changes without any registered port calls, indicating semi-dark ship-to-ship engagements; GNSS manipulation – this was a common combination of DSPs in 2022.

So while we did see a significant decrease in direct port calls in the UK, EU, and U.S. since the war began, the number of shipments arriving through STS engagements has remained steady, despite the ban and the price cap regulations.

This is likely related to the “dark fleet,” a group of vessels operating in the shadows by using DSPs, such as GNSS manipulation, to move sanctioned commodities.

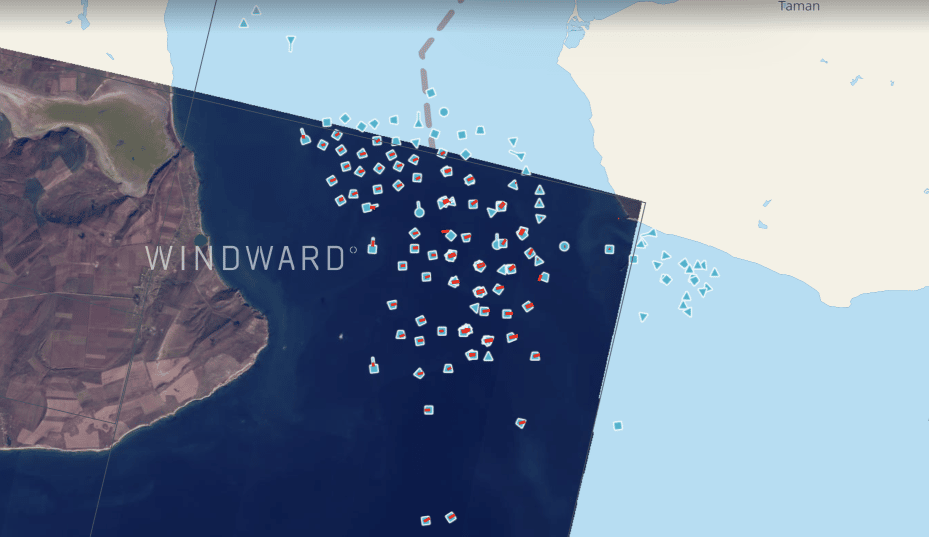

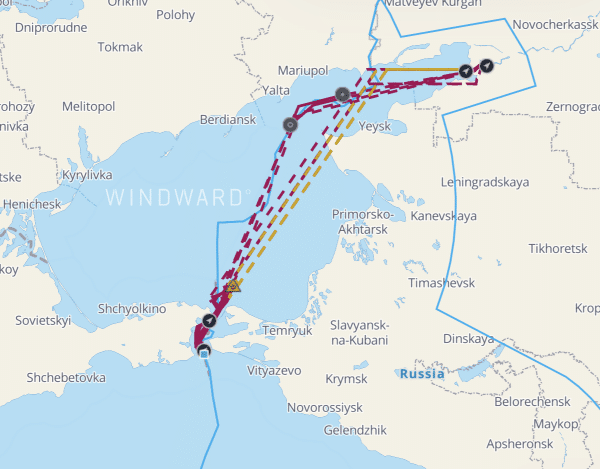

Also, the number of dark activity incidents by cargo vessels in the Azov Sea have been at an all-time high in 2022-2023.

While the STS operations at Kerch are in accordance with seasonal trends since 2021, the dark activity near Crimea right before the meeting is what raises the probability of illicit operations.

Another indicator that these STS engagements in Kerch go beyond the seasonality trend, and are in fact driving grain smuggling out of Ukraine, is the involvement of crane vessels in these meetings. There were three (monthly average) bulk/general cargo vessel meetings with crane vessels in Kerch prior to the war. That increased to 5.2 meetings (per month) after the invasion.

Drilling Down into How Grain Smuggling Works

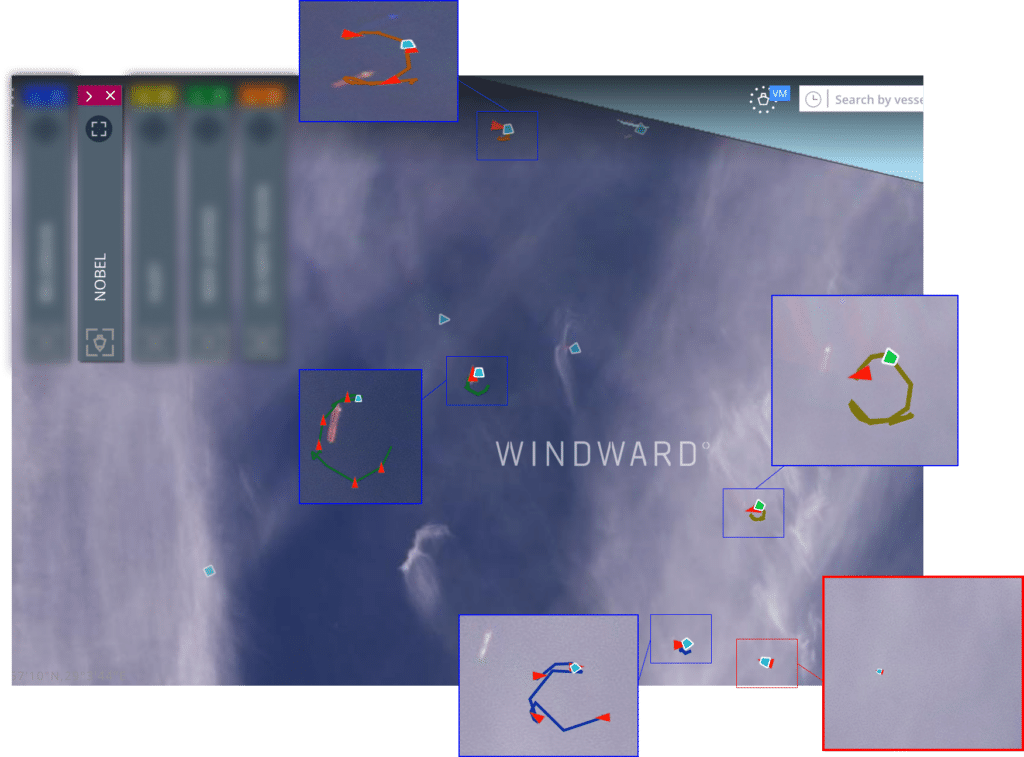

By using Windward’s multi-source investigation tools, we were able to identify an alleged grain smuggling operation, and highlight the important role of crane vessels in these raids.

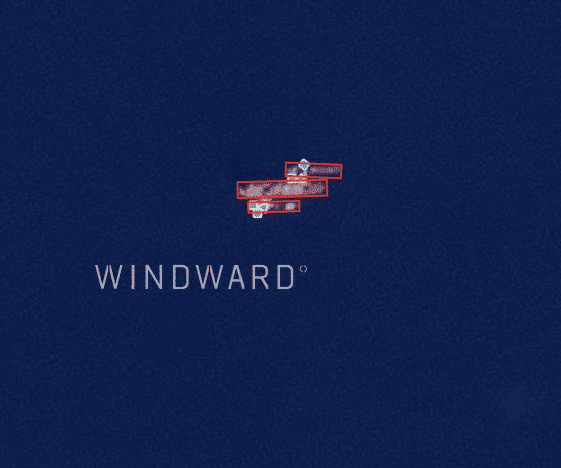

We used the Planet Labs layer, with its integrated object detection capability, to look at the meetings happening at Kerch.

We were able to identify a meeting between six vessels – four cargo vessels and two crane vessels. One of the vessels was identified as the cargo vessel that brought in the smuggled grain – it engaged in a dark activity in the Azov Sea just days before the meeting.

The other two cargo vessels then departed Kerch with the stolen grain and delivered it to Morocco and the Arabian Gulf.

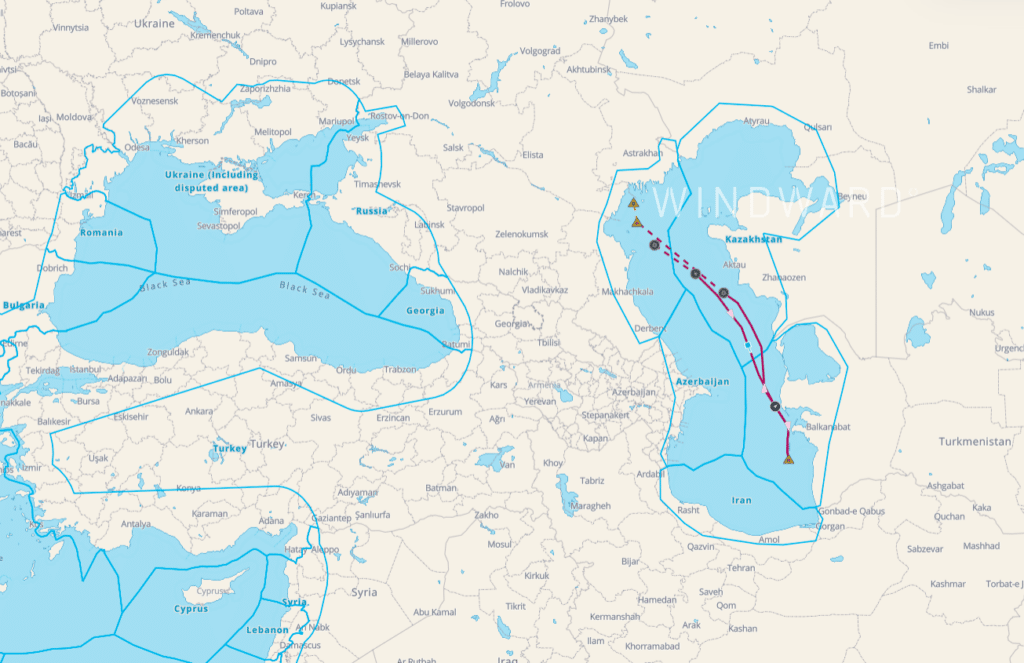

Another interesting insight that supports this theory becomes clear when we look at the Volga and Don passages that connect Iran and Russia through the Caspian Sea – 35 cargo vessels passed through these passages in 2021 (yearly average), but this grew to 50 in 2022 – a 42% increase.

While these visits seem to follow seasonal patterns, the overall number of visits in the relevant season has greatly increased:

Instructive Case Study

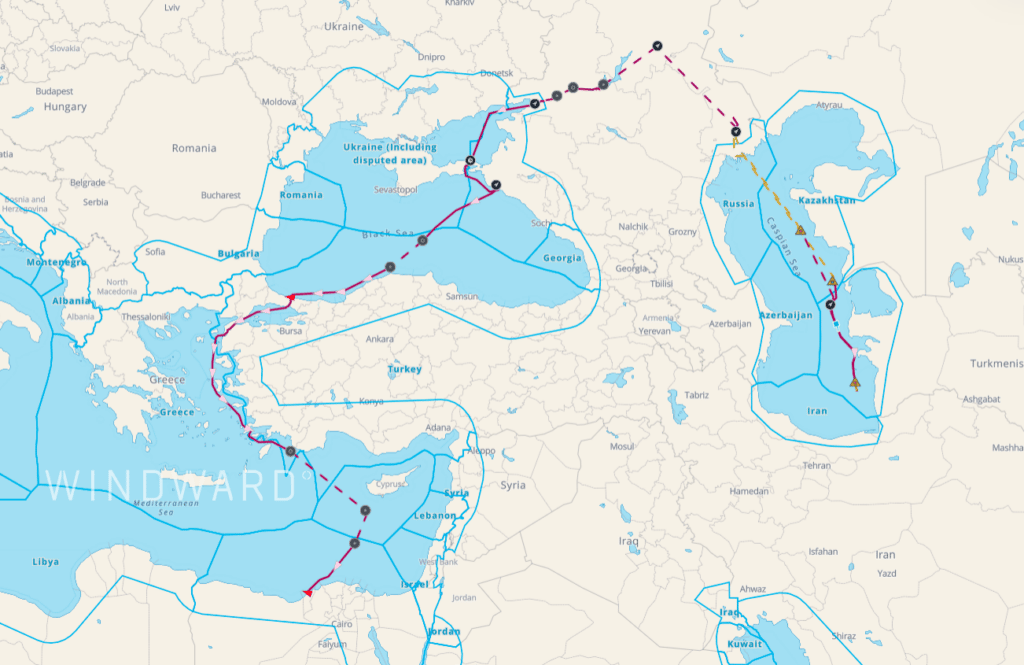

A 103-meter general cargo vessel sailing under the flag of Russia has previously operated in the Mediterranean Sea, the Black Sea, and the Caspian Sea. The vessel is owned by a Russian company.

According to open sources, this vessel previously participated in grain smuggling from Ukraine to the Eastern Mediterranean. On June 18, 2022, the vessel conducted dark activity in the Black Sea, within the Turkish exclusive economic zone (EEZ). The ship’s dark activity ended in the Ukrainian EEZ 19 days later on July 6, approximately 50 nautical miles from the Sevastopol port in Crimea. The vessel’s draft was updated following the dark activity, indicating that cargo may have been loaded during the dark activity.

The vessel then sailed through Bosphorus and Turkish waters, reaching Cyprus on August 14, 2022. On that day, the vessel went dark in Cyprus’ EEZ. Twenty-two days later, on September 5, the vessel’s transmissions resumed in Syrian waters, 15 nautical miles from the port of Tartus.

Following this dark activity, the vessel’s draft decreased, suggesting that cargo may have been offloaded. The vessel then returned to the Black Sea, where it continued to operate, while occasionally visiting Russian ports in the Sea of Azov.

In October, the vessel sailed into the Caspian Sea and conducted three separate dark activities ranging from two to five days in length. The first occurred in the Turkmenistan EEZ, approximately 100 nautical miles north of the Amirabad, Iran port.

In November, the vessel made a port call to Novorossiysk, Russia, before sailing to Egypt and calling port at the port of Alexandria. While at the Alexandria port, the vessel docked in an area where Russian cargo vessels that have been previously implicated in the movement of arms have docked in the past.

In December, the vessel began operating more in the Caspian Sea, making calls at the Russian ports of Rostov-on-Don and Astrakhan on December 10-12, respectively. Between December 18-23, the vessel conducted dark activity in Turkmenistan, 98 nautical miles north of the Amirabad, Iran port. The vessel engaged in similar dark activity in the same general area of Turkmenistani waters between January 8-17, 108 nautical miles north of the Amirabad, Iran port. The vessel updated its destination on January 18 to Makhachkala Port, Russia. The vessel then went dark for nine days between January 19-28 in Russian waters, approximately 100 nautical miles south of Astrakhan in Russia. Its draft decreased following this port call, which could suggest that the vessel offloaded cargo during the dark activity.

The vessel’s last port call was at Astrakhan on January 29 and is currently experiencing signal loss.

Iran’s Caspian Sea ports of Anzali and Amirabad have been implicated as origin points for weapons being smuggled from Iran to Russia. The Russian Caspian Sea ports of Astrakhan and Makhachakla have been implicated as the ports receiving these weapons. The vessel’s prior participation in grain smuggling from the Black Sea to Syria suggests its overall participation in activities related to Russian smuggling during the ongoing war.

Given the vessel’s history of grain smuggling, and its multiple dark activities in areas near the port of Amirabad, Iran, and the ports of Astrakhan and Makhachakla, Russia, it is possible that the vessel could have participated in illicit activity related to weapons smuggling in the Caspian Sea.